For these last few weeks of leave, I have found myself having a particular kind of reading experience. In both discovering and revisiting scholarship on computational literary studies, I have had a similar cycle of thoughts:

First, my mind is blown by the way that what I'm reading completely addresses my questions and points my thinking in a clearer direction.

Second, I am crestfallen, disheartened that I did not discover this sooner (in the case of new readings) or didn't recognize how important or useful it would be the first time I read it (in the case of pieces revisited). How many hours/days/weeks/months could I have saved if I had only read or understood this sooner?

But third, importantly: I consider the possibility that it is perhaps only because of these hours/days/weeks/months spent learning that I am now able to recognize the value of these pieces for my thinking. A lesson our modernist friend (?) TS Eliot tries to impart:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

I will attempt to give some examples that both demonstrate what I've been up to and encapsulate my take-aways from all this exploring, as a fitting form for this, my last dispatch from research leave.1

Example number 1: Canonicity

When you start trying to create a corpus for the study of canonically modernist literature, you think your problem is gathering clean full text, but your real problem is deciding how to define "canonical." For your entire life as a student and practitioner of modernist studies, you have operated assuming the reality of a category of writers called "canonical modernists." These are the writers that were on your very first modernism syllabus, second year of undergrad, of course. And a few others, surely there are a few others, enough others to make a respectably sized corpus, right?

Well, not really, no. It turns out to be a short list, and an even shorter one if you are a deity-forsaken US Americanist determined to make a stake in the thoroughly transatlantic terrain of modernism.2 Also, they are just so different from each other. In a corpus of the size I have, when I run a clustering algorithm in my embedding model to see what words are closest to each other in the semantic space modeled by word vectors, I can tell which ones are produced by Gertrude Stein texts even without character names.

So, when I found myself reading JD Porter's "Popularity/Prestige", pamphlet 17 from the Stanford LitLab, I was prepared to feel the truth of these lines in a way I hadn't before:

"canons have in common a simplistic structure. They are essentially binary, a list of names at the entrance to the club: You’re either in or you’re out. Perhaps you belong in some other canon, but that one will have the same logic of two states, inclusion and exclusion. That kind of organization quickly leads to unsatisfactory outcomes if the goal is to compare the canon to the archive. A canon of thousands of books, like the one ultimately used in Pamphlet 11, could easily include Ulysses and Frankenstein, but what do these two novels really have in common? If the goal is to find morphological signatures of canonicity, does it really make sense to assume that they are more like each other than like various things in the archive, which surely includes forgotten modernist experimental novels and vanished examples of Gothic horror?"

Porter's proposed solution is to look at canonicity as function of prestige and popularity: you either need to be really high in one or above average in both. His proxies for these are the number of reviews of an author's works on Goodreads (popularity) and the number of articles in the MLA International Bibliography with the author listed as the Primary Subject Author (prestige). Put one measure on the x axis and one measure on the y axis and boom, you have canonicity space.

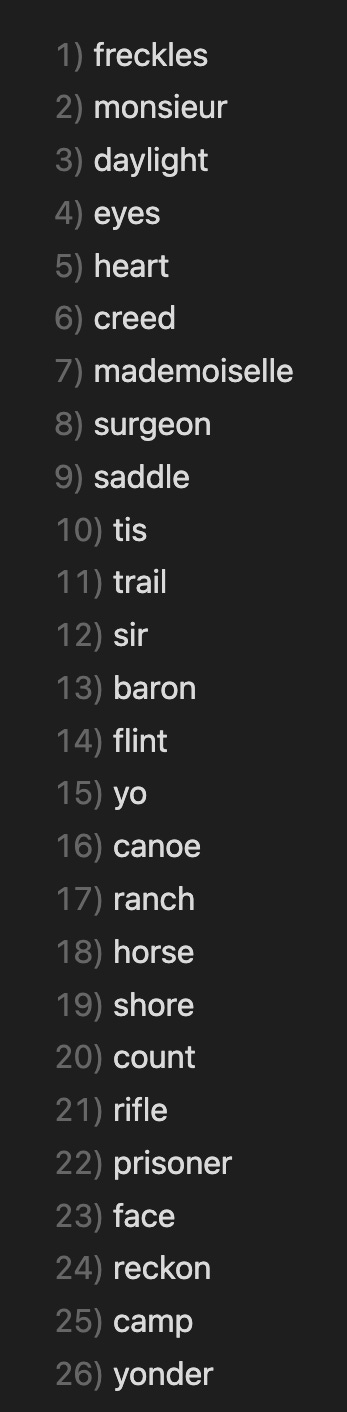

While this solution doesn't sound like one that would work for me, it leads Porter to several insights that have allowed me to return to my corpus building. Perhaps most centrally, the books outside the canon are probably just as heterogenous as the books in the canon, so if I want my non-canonical corpus to be a flatter field, random sampling is probably not the way to go. Because in a random sample, one Western will really skew your keywords:

Also, gratifyingly, Porter, too, finds that while his proxies usefully cluster heavy hitters of many periods together (like the Romantics and the Victorians), modernists are weird:

"Not every grouping is quite that successful; the Modernists do occupy the sort of prestigious canonical position one might expect, but they are fairly widely dispersed."

Number 2: Significance

My last newsletter was a narration of a first return to this topic. After having taken an actual statistics course, could I recognize and address a significance question when it arose in the wilds of my own work? This turned out to be a somewhat laborious exercise in remembering that Chi-squared test existed.

This past week, I worked on refining the list of keywords to compare across embedding models for modernist and non-modernist fiction. The method I used in the significance newsletter was based on my own calculations using word frequencies. There's also a built-in method in one of the softwares I use, AntConc. I decided to try this method as a second source of potential keywords, and I pushed myself to try to understand what it was doing behind the button clicks. Now, I've tried to do this before--dig into the documentation to find out exactly how AntConc calculates keywords. But even post-statistics class, I found myself unable to follow the documentation. But I tried again, and this time, with my own personal Chi-squared adventures behind me, I had enough of a mental toehold to make it through the opening paragraphs on contingency tables and realize that all of the formulas following these tables were different ways of interpreting them. Indeed, Chi-squared was one of them, and one of the methods I could choose in the tool settings to produce the results.

Realizing I could set that parameter with confidence and understanding felt like a big win.

Number 3: Josephine Miles

A colleague and I are considering a future grant application, and one of the elements of this application is an environmental scan of efforts in the area of computational text analysis relevant to our fields. In true first-draft-brain mode, I started writing this with the digital humanities version of "for as long as human beings have existed...": "since Robert Busa began tabulating Aquinas’s concordances...". Then I had a memory of a piece I had run across while reading another dispatch from the LitLab, that referenced Josephine Miles as the ur-distant reader rather than Busa, an alternate and at least equally plausible history outlined beautifully by Rachel Sagner Buurma and Laura Heffernan. Returning to their piece and actually reading it this time, I found in Miles a patron heroine. Miles was a literary scholar, a developer of quantitative methods, and an influential poet. She started counting in grad school when she was studying Wordsworth, and she kept on counting, even when it wasn't cool, and it certainly was never easy. She worked steadily and collaboratively at both data creation and data analysis:

"Miles saw concordances and machine indexing as a core part of literary criticism, for they could help scholars to a broader view of comparisons between poems and poets. And Miles’s distant reading work was not only literary, it was in an important sense modernist: her work tested and overturned some of her generation’s defining accounts of modernist and metaphysical poetry as 'hard' or 'concrete.'"

For Miles, loving poetry meant writing it and counting it. Sagner Buurma and Heffernan put it beautifully: "Miles, drawn in two directions, made a third." Reading this, I realized I'd like to be able to say something similar of myself one day.

These examples span method, math, and history. They all share the dynamic of learning, returning, and learning more. So I think they are a fitting end of leave as I have been so fortunate to have it, and less a beginning of something new than a continuing of continuing.

Hopefully not my last ever, but my last for at least six years

If I had fully understood just how small a slice of the job market Venn diagram I was carving out with this speciality...I hope I wouldn't have changed anything, I am very happy right where I am.

Subtle shoutout to Jesse Matz, I see.